U.S. worker program brought families north from El Bajio, Mexico and today they thrive here.

Sun Post News San Clemente, July 6, 2013

By Fred Swegles

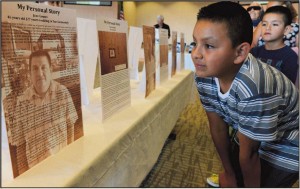

Dionisio Gomez, 10, and his brother Allan, 7, look at their father’s biography in an exhibit at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic Church on generations of families who migrated from El Bajio, Mexico, to San Clemente. About 1,500 of San Clemente’s 64,000 residents can be traced to this multigenerational migration.

About 1,300 miles southeast of San Clemente lies El Bajio de Bonillas, a Mexican town on the outskirts of Silao where a U.S. government Bracero Program office used to recruit Mexican laborers. Today, El Bajio has a reported population of 2,732 people. But the tiny town has spawned a large footprint, helping to weave the social fabric of modern-day San Clemente.

Orange County Human Relations estimates that 1,500 of San Clemente’s 65,000 residents have roots in the Mexican town, the result of generations of migrations from El Bajio that began in the 1940s with braceros. When the U.S. government sponsored program ended in 1964, many workers stayed, and brothers, sisters and cousins kept coming.

“Younger generations started to immigrate, following their relatives,” said Edgar Medina, community-building program supervisor with OC Human Relations. “They chose San Clemente as their town … because of the weather … a sense of town … a need for workers.”

The staff at OC Human Relations, a nonprofit that promotes respect and understanding among cultures, has come to know San Clemente’s El Bajio community well through outreaches into San Clemente’s Spanish-speaking neighborhoods.

Fourth and fifth generations of families from El Bajio call San Clemente home, Medina said. They are people of faith, people who work hard, people who strive to raise responsible children. “They don’t go to the government for help,” Medina said. “They resolve their own problems.”

Amazed to learn how many extended families and friends trace their origins to El Bajio, OC Human Relations launched a project in 2012, inviting people to share their stories and put together a booklet, a CD and an exhibit titled “El Bajio to San Clemente: An Inter-Generational Exploration of a Cultural Journey.”

PHOTOS: KATIE DEES, ORANGE COUNTY REGISTER

Jose Gomez, 46, stands outside his restaurant, El Jefe Cafe, in San Clemente. Gomez was born in El Bajio, Mexico, and has lived in San Clemente since he was 18.

SUCCESS STORY

Jose Gomez, 46, recalls growing up in a one-bedroom house in El Bajio with eight brothers and sisters. They had no television. The town had one telephone.

“As a child, I heard the word ‘north’ and saw many men returning for the holidays, and I wanted to follow them because in town, there was only poverty,” Gomez told OC Human Relations. “I came to San Clemente in March 1986. I was 18 years old.”

He didn’t speak English then. Learning English was a struggle, as he worked every day through the back door of various San Clemente restaurants. Today, he apologizes for his accent, but he and his wife are U.S. citizens, as are their children, and they feel pride that they are contributing to the San Clemente community. Gomez now owns his own restaurant, El Jefe.

A BETTER LIFE

Francisca Perez, 64, recalls her upbringing in an adobe house near a dam where kids swam. Her brothers left El Bajio for San Clemente 46 years ago. She followed 26 years ago.

“I wanted to give my children a better life,” she told the human relations group. “I’ve been able to support them by working in restaurants, as a florist, cleaning houses and in a hospital for the elderly. I’ve always had a job and always provided food for my children. My daughter Alma Solis attended Saddleback College. I am very proud of her.

“It’s a big challenge not to be legal here. At the beginning, most people come over without their children, and it’s difficult to be away from your children. We don’t have medical benefits or insurance, and finding housing is also a challenge. The racism is humiliating … due to fear of deportation, we would lock the doors and would not go out to the street. Now the situation has improved greatly. We do a lot of hard work for low wages, socialize in and out of our community. We are religious and spiritual. Our families are healthy and united.”

Alison Solis, 17, addressed a recent gathering at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic Church, where the El Bajio exhibit debuted. “I was born and raised in San Clemente,” she said. “My dad is from El Bajio, Guanajuato, and my mom is from Guatemala.” A recent graduate of San Clemente High School, she will enroll at San Jose State University to study environmental science.

MOVING FORWARD

Denise Obrero, housing specialist with the city of San Clemente, said the El Bajio project is an important work that the organizers hope to share with students in San Clemente’s elementary schools. “When they learn about San Clemente’s history,” she said, “they can also learn about El Bajio. San Clemente is doing a lot of good, positive work in terms of community-building.”