April 4, 1968: Civil Rights icon, Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated on the balcony of his hotel room in Memphis, Tennessee. James Earl Ray is convicted of the murder in 1969

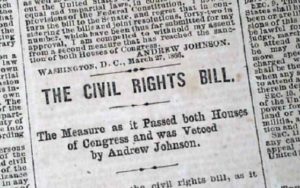

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 became law on April 9, 1866. President Andrew Jackson, a Democrat, attempted to veto the bill, but it was overruled by the Republican controlled Congress. The act granted citizenship and the same rights enjoyed by white citizens to all male persons in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” Its transformational legacy would surface over the course of 150 years, a period marked by entrenched resistance as well as heroic support. However, the activities of organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan undermined the workings of this act and it failed to guarantee the civil rights of African-Americans.

April 11, 1968: President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act, providing equal housing opportunity regardless of race, religion or national origin.

May is Asian-Pacific American Heritage Month – a celebration of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States. A rather broad term, Asian-Pacific encompasses all of the Asian continent and the Pacific islands of Melanesia (New Guinea, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji and the Solomon Islands), Micronesia (Marianas, Guam, Wake Island, Palau, Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and the Federated States of Micronesia) and Polynesia (New Zealand, Hawaiian Islands, Rotuma, Midway Islands, Samoa, American Samoa, Tonga, Tuvalu, Cook Islands, French Polynesia and Easter Island).

Like most commemorative months, Asian-Pacific Heritage Month originated in a congressional bill. In June 1977, Reps. Frank Horton of New York and Norman Y. Mineta of California introduced a House resolution that called upon the president to proclaim the first ten days of May as Asian-Pacific Heritage Week. The following month, senators Daniel Inouye and Spark Matsunaga introduced a similar bill in the Senate. Both were passed. On October 5, 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a Joint Resolution designating the annual celebration. Twelve years later, President George H.W. Bush signed an extension making the week-long celebration into a month-long celebration. In 1992, the official designation of May as Asian-Pacific American Heritage Month was signed into law.

The month of May was chosen to commemorate the immigration of the first Japanese to the United States on May 7, 1843, and to mark the anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. The majority of the workers who laid the tracks were Chinese immigrants.

Learn more about Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

Mental Health Awareness Month (also referred to as “Mental Health Month”) has been observed in May in the United States since 1949, reaching millions of people in the United States through the media, local events, and screenings. During the 1960’s, this annual, weekly campaign was upgraded to a monthly one with May the designated month.

Mental Health Awareness month has a goal of building public recognition about the importance of mental health to overall health and wellness; informing people of the ways that the mind and body interact with each other; and providing tips and tools for taking positive actions to protect mental health and promote whole health.

Learn more about Mental Health Awareness Month

May 3 is World Press Freedom Day, proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in December 1993. A free press is the bedrock of a democratic society and perhaps more crucial now than ever. “As the [COVID-19] pandemic spreads, it has also given rise to a second pandemic of misinformation, from harmful health advice to wild conspiracy theories. The press provides the antidote: verified, scientific, fact-based news and analysis.” – UN Secretary-General António Guterre

3 May acts as a reminder to governments of the need to respect their commitment to press freedom and is also a day of reflection among media professionals about issues of press freedom and professional ethics. Just as importantly, World Press Freedom Day is a day of support for media which are targets for the restraint, or abolition, of press freedom. It is also a day of remembrance for those journalists who lost their lives in the pursuit of a story.

#WorldPressFreedomDay

May 17, 1954:Brown v. Board of Education, a consolidation of five cases into one, is decided by the Supreme Court, effectively ending racial segregation in public schools. Many schools, however, remained segregated.

May 21st is the World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development. The UN says, “Three-quarters of the world’s major conflicts have a cultural dimension. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability and development.” Locally and nationally we too often see how cultural clashes create conflict. All of us have a role to play in building bridges of understanding to create peaceful and thriving communities.

Cultural diversity is a driving force of development, not only with respect to economic growth, but also as a means of leading a more fulfilling intellectual, emotional, moral and spiritual life. This is captured in the seven culture conventions, which provide a solid basis for the promotion of cultural diversity. Cultural diversity is thus an asset that is indispensable for poverty reduction and the achievement of sustainable development.

At the same time, acceptance and recognition of cultural diversity – in particular through innovative use of media and Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) – are conducive to dialogue among civilizations and cultures, respect and mutual understanding.

More info at: https://www.un.org/en/events/culturaldiversityday/